People are talking about reworking the definition of “planet” again. To be honest about it, did they ever stop after the Pluto debacle? I’ve been in it, too, slamming the truly idiotic definition of a planet asserted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

People are talking about reworking the definition of “planet” again. To be honest about it, did they ever stop after the Pluto debacle? I’ve been in it, too, slamming the truly idiotic definition of a planet asserted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Recently, however, it’s not the bottom end of the definition of planets (where Pluto got the boot) that’s the issue, it’s the top end where gas giants fade into stars.

I’ve thought about that boundary as well. In fact, I had already worked out a completely new (and, I believe, more rational) system of classifying heavenly bodies for an unpublished preface to the science fiction novel Xenes. In fact, I may include it as an appendix. But, I’ll share it here, outside the narrative context.

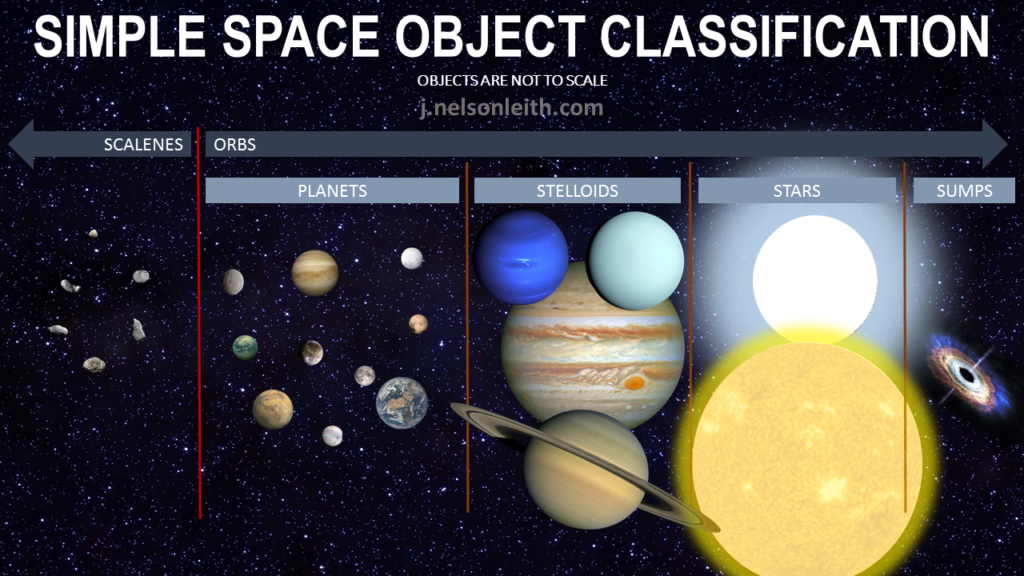

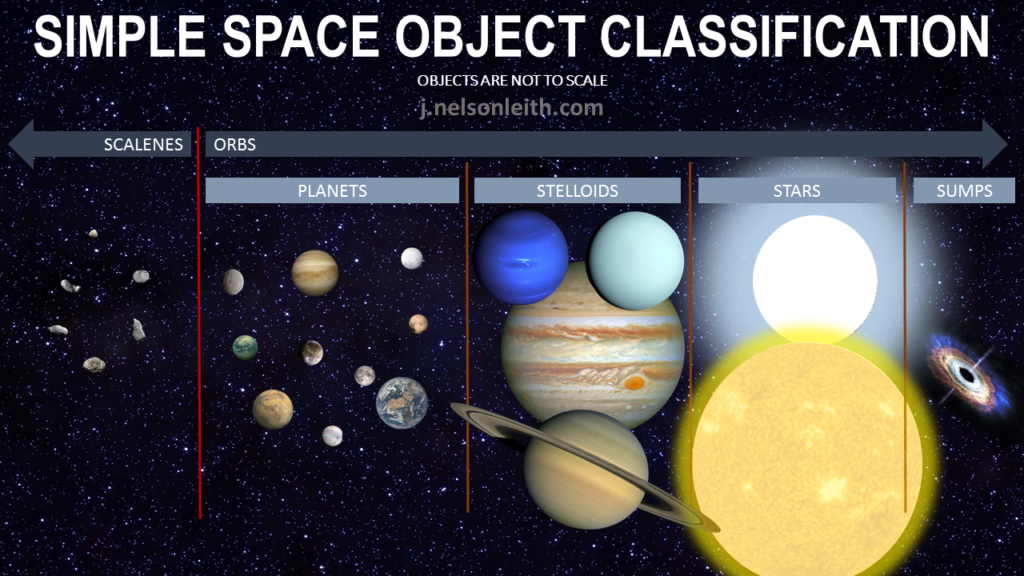

The basic idea was to conduct differential diagnosis in reverse. First divide everything we find in space into two distinguishable halves, and then repeat that process until there was a workable typology. Specifically, a workable typology that had nothing to do with where the object was in relation to other objects, i.e., what the object was orbiting or whether it had “cleared its orbit” of other objects. A typology of what objects are, not where they are.

IS IT ROUND?

The first division is between orbs, objects large enough for hydrostatic equilibrium to make their surfaces essentially round, and scalenes, from the Greek for uneven, rough, rugged. The standard for hydrostatic equilibrium is present in the IAU’s typology, but they staple on expectations about the object’s path in space, relational standards to other objects that really should have no place in determining what an object is.

Orbs would include everything from what we now call dwarf planets through planets, gas giant planets, and stars to black holes.

Scalenes would include basically everything else, from asteroids and comets all the way down to dust. Anything that isn’t massive enough to become round through hydrostatic equilibrium.

Now, this scalene-orb divide puts Pluto and other “dwarf planets” on the same side as Earth, Jupiter, stars, and black holes. Which is a fairly diverse bunch of things. So, we need to apply the same diagnostic technique to orbs.

DOES IT HAVE A SOLID SURFACE? (OR…)

Having a “solid surface” is a problematic definition. It certainly puts Pluto and Earth in the same category, right? But what about ice giants like Neptune and gas giants like Jupiter which, under all that atmosphere, are believed to have a solid core? Also, the solid surfaces of some objects conceal a huge mass of liquid, like the Earth’s rocky mantle or the water oceans believed to exist inside Ceres and Enceladus.

So, let’s do this. An orb is a planet if its volume is dominated by solids and liquids. Regardless of where it is in relation to other objects. Thus, regardless of what it orbits or whether it has “cleared its orbit,” whatever the hell that means.

This puts off our term for orbs like Jupiter and Uranus for later, of course. But, this also means not only that Pluto and other trans-Neptunian orbs would be planets, but including orbs like Ceres, Titan, Ganymede, and even Earth’s moon Luna. We can still use the word “satellite” as a modifier to describe planets that orbit things that aren’t stars. But they would be satellite planets. And, we could colloquially use “moon” to describe planets and scalenes (like Deimos, a satellite scalene of Mars) that orbit things that aren’t stars, but this would no longer strictly be a scientific term.

This approach might seem ambitious, but it’s also rational and scientific. A thing is what it is based on its own characteristics, not based on where it is in a spatial relationship. A can of beans doesn’t become something other than a can of beans because you put it on top of a box of macaroni or in a shelf beside other cans. This definition of planet is the rational and scientific approach, even if it upends our traditional ways of thinking.

A planet would be any orb with its volume dominated by solids and liquids. Which brings us to the next boundary.

IS IT DOMINATED BY GASES?

This seems like a straightforward boundary. But, are we talking dominated by mass or volume? Considering the relative mass of solids and fluids, I would select volume.

First, terminology. I reject “giant planet” for the same reason I reject the IAU’s “dwarf planet.” Both “giant” and “dwarf” are modifiers. Being a “dwarf planet” means Pluto is still a kind of planet, a grammatical reality that the IAU doesn’t seem to understand. It’s one of the things that makes their attempted demotion of Pluto logically absurd. Calling orbs like Saturn and Neptune “giant planets” would be, frankly, dumb.

Instead, given the hazy boundary between what we now call giant planets and small stars, I would call objects dominated by gases stelloids. They certainly aren’t in the same category as planets like Titan and Mars but, although their make-up differs significantly from plasma-dominated stars, they resemble stars more than planets in their form and internal dynamics.

This obviously also defines the next category, stars, which would be orbs dominated by plasma. Both the stelloid and star categories have obvious internal boundaries that need addressed, but the basic boundary between stars and stelloids is relatively easy to navigate.

The fuzziest boundary is between planets and stelloids, given that we should expect a significant gray area between smaller stelloids like Uranus or Neptune and planets with thick atmospheres like that of Venus, which is 90 times more dense than Earth’s. We can work that out as more planets are discovered outside our Solar System. The standard of volume, I believe, is the best standard.

And this, beyond stelloids and stars, bring us to our final category.

DOES IT HAVE AN EVENT HORIZON?

At a certain point, the mass of a plasma-dominated orb bends physics to create the infamous event horizon. This is the only place where physics makes having the standard be mass-based rather than volume-based bring sense to the typology. At this boundary, it’s mass that changes the nature of the orb.

The current system refers to these objects as “black holes,” which is a strange designation considering the radiation that exudes from them. Given the one-way nature of the event horizon (setting Hawking radiation for the moment) I suggest we call these object “sumps” because matter and energy drains into them. This is also a much less sensational term that doesn’t subject itself to pseudoscientific, “I LOVE SCIENCE” style of goofy speculation.

So, below is a graphic outlining the typology described above. I hope you see hope for astronomy in this and share it far and wide.

People are talking about reworking the definition of “planet” again. To be honest about it, did they ever stop after the Pluto debacle? I’ve been in it, too, slamming the

People are talking about reworking the definition of “planet” again. To be honest about it, did they ever stop after the Pluto debacle? I’ve been in it, too, slamming the

In a pharmacy, the three youngest Girls are preparing for a romantic weekend with three men. Blanche hints that they should take “protection” with them. After Rose guesses incorrectly what Blanche means (three times!) Dorothy blurts out:

In a pharmacy, the three youngest Girls are preparing for a romantic weekend with three men. Blanche hints that they should take “protection” with them. After Rose guesses incorrectly what Blanche means (three times!) Dorothy blurts out: Everyone loves the zombie novel. No, I don’t mean a novel about zombies. I mean the novel itself as an artform, which walks on undeterred by premature declarations of its demise.

Everyone loves the zombie novel. No, I don’t mean a novel about zombies. I mean the novel itself as an artform, which walks on undeterred by premature declarations of its demise.

Everybody has their Top Ten lists. Sure, lists are a viral sensation in the Age of the Internet, but let’s not forget that Casey Kasem was counting down our

Everybody has their Top Ten lists. Sure, lists are a viral sensation in the Age of the Internet, but let’s not forget that Casey Kasem was counting down our

Lists of things you should “never say” to this or that group of people are a plague on the Interwebz.

Lists of things you should “never say” to this or that group of people are a plague on the Interwebz.

Reviewing the screenplay for The Wall, a story about a sniper pinned behind a wall by an enemy sniper who clearly knows him, Christopher Pendergraft at Script Shadow makes a fantastic observation on dialogue that every writer needs to read.

Reviewing the screenplay for The Wall, a story about a sniper pinned behind a wall by an enemy sniper who clearly knows him, Christopher Pendergraft at Script Shadow makes a fantastic observation on dialogue that every writer needs to read.