In a recent Guardian rant by Edward Docx (a writer with the odd misfortune of sharing his name with a word processor file extension) the peculiar fantasy that there is a fundamental “difference between literary and genre fiction” is once again stitched together Frankenstein-like from bits of half-dead prejudice, tiresome artifice, and simple humanistic hubris.

In a recent Guardian rant by Edward Docx (a writer with the odd misfortune of sharing his name with a word processor file extension) the peculiar fantasy that there is a fundamental “difference between literary and genre fiction” is once again stitched together Frankenstein-like from bits of half-dead prejudice, tiresome artifice, and simple humanistic hubris.

It is time to double-tap this stubborn literary zombie and put an end to its virulent intellectual jaundice once and for all.

I’ve already tackled this silly bogeyman once, discussing Karen Essex‘s Dracula in Love, but let’s start fresh with Docx’s primary criticism of genre, and his primary error:

Even good genre … is by definition a constrained form of writing. There are conventions and these limit the material.

Docx is being absurdly parochial and chauvinist here. Are there no conventions in so-called “literary” fiction?

_

One Genre Among Many

As linguist Max Weinreich reminded us, a language is simply a dialect backed by an army and navy. Likewise, the “literary” is simply a genre backed by academia and a publishing establishment, specifically (for English fiction) the soldiers of the MFA and the twin armadas of New York and London.

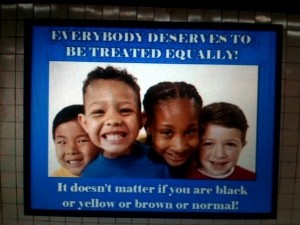

Essentially, self-styled literary snoots like Docx are mimicking the same ignorant supremacism as those who insist, “People where I’m from don’t have an accent.” Yes, yes you do.

In her remarkable essay, “The Critics, the Monsters, and the Fantasists,” author Ursula K. Le Guin provides an excellent breakdown of what would be more accurately described as the modern realist genre. Suggesting for the sake of illustration that we turn the tables and “judge modern realist fiction by the standards of fantasy,” she provides the following list of what could reasonably (if unflatteringly) be considered its conventions:

A narrow focus on daily details of contemporary human affairs; trapped in representationalism, suffocatingly unimaginative, frequently trivial, and ominously anthropocentric.

Of these, the spot-on description of modern realist fiction as representationalist is, I believe, the most humbling. If that’s not a “constraining convention” what is?

And, alongside “suffocatingly unimaginative,” it cuts into modern realist literature’s claim to be the best of creative writing, because it is undeniably and categorically the least creative of it.

When a writer outside of modern realism wants to tackle serious philosophical questions, she can invent a new species, a new culture, a new world, a new technology on which to build her metaphors and explore the issues. When a modern realist writer wants to tackle serious philosophical questions, he is much more limited.

For example, we can imagine even the best of modern realist writers, lacking other writers’ Freedom from constraints and conventions, opening a newspaper and simply picking a contemporary political controversy like, say, the ecological effects of mountaintop removal in coal-mining regions.

Talk about a “constrained form of writing” in which “conventions … limit the material.” And yet, still manages to be considered “literary.”

_

The Instant Cake Mix of Literature

Now, I don’t have anything against the modern realist genre. I’ve written a bit of it, in fact. It is an honorable and enjoyable genre.

But, there is simply no denying that it is far easier to write a tale like “Swept” about a little girl upset about the obliviousness of her parents than a tale like the Observer’s Casebook about a guy with an invented job in an invented world investigating invented crimes for an invented organization.

Especially if you’re concerned about carefully maintaining the coherence of the story’s inventions. For modern realist fiction, most of this work has already been done for you, by Reality Itself and the billions of human beings who live there, exploring, testing, erring, and troubleshooting the phenomena that modern realists accept as the constraining conventions of their fiction.

For example, when writing Swept I didn’t have to work out whether little girls would get upset when their parents behaved callously. Nor did I have to integrate the concepts of cats, staples, mailbox doors, raincoats, glass windows, curtains, refrigerators, jeans, cake pans, and frosting. Compared to a carefully written plot in a non-realist genre, plotting in the modern realist genre is easy-breezy.

And, the literary quality of the writing is simply frosting on that cake.

Sure, there are multitudes of hack writers outside of modern realism who opt to simply import character types, places, and plot elements directly from previous best-sellers in their genres, but in order to qualify as a realist writer you must import character types, places, and plot elements from reality. There’s no opt about it. The constraints of modern realist convention won’t allow you any inventiveness in that regard.

_

For Every Sound, Many Echoes

And these hack “genre” writers, like the countless Tolkien copycats out there — we need not pretend that their derivative elf-and-apocalypse scribblings are creative writing, or that they defy the constraints of convention.

But Tolkien’s scribblings were and did. Every copycat convention requires a precedent (they don’t just appear by magic, even in the fantasy genre) and every precedent is by nature inventive.

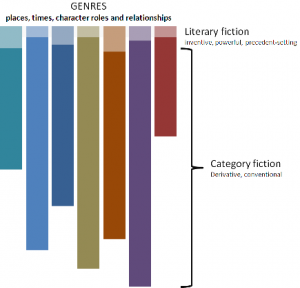

So, in order for a genre to contain highly conventional material (in the sense of being derivative — let’s apply the term “category fiction” specifically to this stuff) it must also contain inventive, precedent-setting, literary material. The opposite is also true: genuinely good writing will always inspire the copycats of which categories are comprised.

Otherwise, we have to posit some sort of supernatural ex nihilo origin for category fiction, and some sort of spacetime-cracking literary event horizon blocking the creative stuff from radiating streams of emulation.

And, that’s just painfully silly thinking, isn’t it?

For every bearded and bespectacled writer out there trying to pass off a thinly veiled Lord of the Rings remix as original fantasy fiction, and every overheated teen writer (or adult writer with adolescent sensibilities) pushing one more Twilight clone, there’s an MFA or NYC writer trying to pass off yet another humanist narrative essay — with a few tediously introspective characters thrown in — as original modern realist fiction.

_

One Caveat

On second thought, let me play the caveat card. I need to backtrack on that last generalization a bit, because I don’t really believe that every genre contains precisely the same proportion of derivative, category fiction.

On second thought, let me play the caveat card. I need to backtrack on that last generalization a bit, because I don’t really believe that every genre contains precisely the same proportion of derivative, category fiction.

For one thing, publishers have a tendency to drill quickly into any narrative aquifer that bubbles profitably to the surface of literature, transforming those wellsprings of fresh fiction into piped-and-processed tap water. Some of these sources are certainly more easily tapped (or have greater force) than others, and are therefore more productive, leading to higher ratios of derivative category fiction in certain genres.

Likewise, certain genres enjoy more literary-quality production for a variety of reasons, including not only the innocent, personal, stylistic preferences of writers themselves, but also the aggressively conformist attitude of the “literary not genre” elite, which can intimidate the less sturdy among those writers who wish to be taken seriously as literary authors.

Write modern realist fiction or be mocked! (Or worse, ignored.)

_

Regular People and “Ethnics”

However, incidental variation in the literary saturation of different genres does not redeem the prejudice that leads Docx and others to dismiss everything outside of modern realism as benighted, ooga-booga savagery undeserving of the label “literary.”

Nor does it justify the offensive premise that what separates modern realism from other genres is its unique literary aspirations.

The inane redundancy of the term “literary fiction” itself should clue us in to its banal, vacuous elitism. After all, throughout human history chauvinist cultures have assigned themselves names that translate to something like “The People” or “Real Humans” while everyone else were dismissed as “The Tribes.” The same silly prejudice persists today in the United States among those who use “ethnic” as shorthand for “not Anglo-Saxon.”

The inane redundancy of the term “literary fiction” itself should clue us in to its banal, vacuous elitism. After all, throughout human history chauvinist cultures have assigned themselves names that translate to something like “The People” or “Real Humans” while everyone else were dismissed as “The Tribes.” The same silly prejudice persists today in the United States among those who use “ethnic” as shorthand for “not Anglo-Saxon.”

Literary success in any genre, fantasy and modern realism included, invites imitation according to its peculiar forms. Since invention leads to type, type is evidence of invention. Mutations give rise to species, inspirations to doctrine. All genres contain both wheat and chaff, sound and echo, literary and category.

The imitative works certainly deserve a subordinate place in the shadow of their betters, but the more mimics sustained by a particular convention the greater the original innovation must have been to cast such a broad shadow. The very fact of conventional, or category, fiction in genres outside of modern realism is proof of the literary merit in the seed texts, invisible to the tribal prejudices of the modern realist.

_

The Vanishing Point of Diversity

Docx’s conceit also suffers from a perspective bias I like to call the Minneapolis-St. Paul Problem: people tend to overestimate the variety in their local community while underestimating or simply ignoring/denying the variety in distant communities.

So, a resident of either of the Twin Cities is likely to feel that there is a great deal of difference between Minneapolis and St. Paul, while tending to view places like Dallas and Fort Worth, or Raleigh and Durham, or the two Kansas Cities as virtually indistinguishable.

It’s the same bias from limited experience that informs the casual racist’s “they all look alike to me.”

For a less caustic example: most of us have a hard time distinguishing artists in musical genres we don’t like, and the uncanny ability of fans to pick them apart with a single note can be baffling. This has nothing to do with “constraining conventions” in their music, and only a self-absorbed dolt who really doesn’t understand music very well would assume it meant that his own favorite style lacked conventions.

Okay, so maybe that turned out caustic in the end, but self-absorbed dolts deserve it.

This is a basic principle of perspective that representationalist writers should easily understand: things further away from us look closer to each other than they really are, while things near us seem relatively further apart. Representationalist painters figured this out centuries ago.

I suspect Docx can’t see the conventions in modern realist fiction because he’s too close to them. What is so obviously conventional to an objective observer seems widely varied to the vested partisan.

_

The Tactical Obsession

Docx reveals another constraining convention of modern realist fiction when he presents what he dismisses as the “scathing and disingenuous” criticism directed at it from so-called genre types: “there’s no story, nothing happens…”

Since self-styled literary types belong to a modern realist genre we can reasonably describe as constrained by the convention of anthropocentrism — or, more politely, humanism — it is ironic that they seem so allergic to the most critically human aspect of fiction, in fact its raison d’être: the emotional need for a sensible narrative.

Just as a great story with minimal character development and piss-poor writing should be rightly criticized for its literary failings (even if it dances among angels on the pin-head of the New York Times Best Seller list), no well-written, hundred-thousand-word character study with little discernible story deserves entry into the gates of the literary.

So why does modern realism so narrowly focus on these details while dismissing or even openly defying the virtues of the storyline?

It helps to remember that humanism and representationalism grew up side-by-side with scientific reductionism, so this fixation on well-crafted prose primarily at the scale of words and phrases makes genealogical sense. Moreover, this reductionist bent points toward why modern realists fail to see much value in genres that do value the emergent storyline.

Modern realists suffer from what, in military reform circles, is called a “tactical obsession.”

Just like a good war plan, a good story has multiple levels. There is the effectiveness of the writing itself at the tactical level: word choice, sentence and paragraph structure. The artful integration of sounds, semantics, meter, and grammar is the measure of tactical success in writing. A good tactical writer plays with these tools, but she also respects them.

This tactical level is where certain “genre” writers like the ever-ready punching bag Dan Brown are weakest. And truly literary fiction excels at this scale, whether it falls into the modern realist genre or not.

Then there is the effectiveness of the overall plot and setting, the strategic level of writing. As you might have anticipated, this is where the self-styled elites of modern realist fiction often sabotage themselves with quixotic, adolescent, Boomer-culture crusades against “convention,” and therefore where modern realistic fiction tends to be weakest.

There is often, pretty much by design, no story and nothing happens.

_

The Inhuman Stain

The real problem at this holistic scale, for the convention-phobic literary puritan, is that human psychology is geared to narrativize within a certain gamut of potential story-lines and plot devices, just as it is geared to communicate using a certain gamut of potential memes and phonemes.

Ironically for the humanist aspect of modern realist fiction, this narrative instinct likely has evolutionary roots just as language does. Deviate too far from what might fairly be termed an archetypal plot, and the story becomes unsatisfying, inexplicable, and ultimately boring to the human animal.

The same, of course, goes for the tactical level of writing, words and phrases. Bend language too far in a crusade against convention, force too much innovation into your words and phrases, and the language breaks. Sadly, modern realist writers striving for extremes of “literariness” at the level of the writing itself can, instead of achieving tactical mastery, bungle it by overshooting the goal.

It’s not always, as Laura Miller sniffles via Salon, that “strenuously inventive prose would strike them [the non-modern realist] as too much work.” Sometimes it just strikes them as tortured and ugly, an aesthetic and literary failure.

Literature isn’t supposed to be a chore; if the reader has to struggle to figure out what the hell is going on, this means the writer has failed, full stop. “They’re just too dumb/lazy to understand what I’m saying” is an argument better suited for internet flame-wars than serious discussions of literature.

On one hand, this weird jihád against common language brings to mind the gimmick novel Gadsby, written by Ernest Vincent Wright entirely without the letter “e”. If avoiding common English phraseology is a measure of literariness, why wouldn’t avoiding common English letters be?

Short answer: neither are measures of literariness. Both are gimmicky.

On the other hand, this novelty-worshiping standard of literary excellence reminds me of the Hollywood-chic standard of feminine beauty, in obeisance to which so many women burn away all their fat by starving and exercising themselves into jagged skin-sacks of joints and ribs. Is it strenuous, to use Miller’s term? Certainly. Is it beautiful, healthy, or admirable? Not at all.

A little feminine fat — i.e., curves — is natural, beautiful, and healthy for the human physique. Likewise, a little linguistic fat — those common turns of phrase derogated as clichés — is natural, beautiful, and healthy for human expression.

Taken to extremes, of course, either type of fat becomes … let’s just say “problematic.” But, desperately burning it all off for the sake of some artificial, inhuman standard of perfection stinks of literary anorexia.

But, even when modern realist writers of the “literary fiction” sect bake their tactical language just enough without burning it, their concept of effort — not toward good writing as such, but toward the “strenuously inventive” and away from the “constrained conventional” — makes it difficult for them to find any sort of narrative power at the strategic level, creating stories in which “nothing happens” except a tedious barrel-monkey chain of well-written paragraphs.

So-called genre fiction is popular at novel length precisely because it is delicious at novel length. The common reader’s criticism of so-called literary fiction that “it’s beautifully written but I just couldn’t get into it” reflects the tactical obsession, and strategic weakness, of the modern realist writer. Their fiction is well-liked at sentence length because it is most delicious at sentence length, but all-too-often tasteless as chalky water or, worse, intentionally offensive to human sensibilities at the holistic level.

_

Art in Proportion

The real measure of genuine literary quality is not when the story takes place, whether all the species in it exist in the real world, or how the main character accomplishes (or fails to accomplish) her goals. The real measure is how well the author plays with the tools of storytelling without breaking them.

Just as good tactical writing (like that emphasized by non-pretentious vintages of modern realism) avoids cliché without ravaging or abandoning the human language in which it is written, good strategic writing avoids outright narrative mimicry (sorry Terry Brooks) without ravaging or abandoning the human narrative instinct.

Failing miserably at the strategic while succeeding wildly at the tactical does not “literary” fiction make. A stone-worker who sculpts the most elegantly grotesque gargoyles but can’t get a vaulted ceiling to stand on its own should not be praised as a master architect.

Luckily for the modern art of architecture, physics tells us when innovative building techniques fail. A multitude of clinically demonstrated cognitive biases can convince a tribal partisan that the clumsiest pile of literary rubble is in fact a cathedral, so long as the blocks were quarried in a “strenuously inventive” fashion. But, it ain’t so.

Purposefully undermining the strategic beauty of a story in order to angle one’s nose to arc over “convention” is not an admirable effort, no matter how carefully one attends to the tactical beauty of the writing. It’s a stunt, a juvenile act of “too cool for school” rebellion that should be laughed at, not lauded.

_

Literary Aspartame

So, how can a contrarian stunt with a terrible storyline be received as “literary”?

The saving grace for the lit snoot is that, as a substitute for a strategically unsatisfying story, fiction can satisfy an abstract sense of novelty, innovation, and shock effect, but only if you have arduously studied what has gone before — that is, if you approach literature primarily academically.

But, while there certainly is a value in knowing what has been written before, studying the technique of previous bowmen so you can more cleverly miss the bull’s eye they hit is not the measure of a serious archer.

Beyond stylistic contrarianism, however, fiction with a bad (or non-existent) plot can substitute for a truly literary story by appealing instead to the moral warrants of particular tribe — or, less generously, to the dogma of a particular political ideology.

To provide an example from a genuinely good story in the modern realist genre which does not suffer from tortured prose or strategic failure of plot, take Brokeback Mountain — both the short story and the film, since Proulx was so enthusiastic about the screen adaptation.*

A beautiful, touching story? Absolutely.

Literary fiction? Without a doubt, both tactically and strategically.

Hyped well beyond its considerable merits by the politics of America’s cultural Brahmins? You’d have to be a member of that caste not to recognize it.

The realism of the modern realist genre probably has a lot to do with this hyping factor: the subject matter of modern realist fiction is so (un-inventively) close to the memoir, the essay, and the editorial that it takes on a sort of abstracted importance beyond its literary value.

Sure, plenty of the popularity of “The Sneeches” rests partly on its commentary about bigotry, but nobody considers it important in the struggle against discrimination against people without “stars upon thars.” Why? Because there are no such things as Sneeches.

If really good fiction like Proulx’s can be boosted to the Messianic heights of the “culturally transformative” by the political sentiments of the star-bellied literati, really bad fiction can certainly be elevated to mere “literary” status by the same social mechanism.

In other words, not only is Docx’s “literary” really just another genre among many, better described as modern realism, there’s plenty of reason to be respectfully skeptical of the claims of modern realist partisans to the peculiar literariness of works in their genre.

And certainly enough reason to reject completely their claims that other genres lack literary excellence.

_

* To be honest, the reasons I turned to Proulx were not only that I was deeply impressed by the remarkable vigilance she displayed when inspired to write Brokeback Mountain (I won’t spoil this anecdote, so you’ll have to go find it yourself) but also because she too has a name ending peculiarly with an “x”.

Janan Sabila

December 19, 2010 at 2:07 pm

This is wonderful! But there is so much and so compressed. Would you break it up and expand it some?