Pyramid scheme? Is that an unsigned writer standing by a publishing bridge with a lighter in one hand and a can of kerosene in the other?

Pyramid scheme? Is that an unsigned writer standing by a publishing bridge with a lighter in one hand and a can of kerosene in the other?

Believe me, what follows is not intended as an accusation of any sort. I have the greatest respect for literary agents, editors, and publishers, who slog through piles of manuscripts that would make me cry like only a grown man can cry: masked in anger and empty threats. I have suffered through enough truly awful writers’ group submissions to know that I could never do what these ladies and gentlemen do on a daily basis.

So, this isn’t about questioning anyone’s integrity. And, it’s not about protecting or promoting my own interests as a writer, which the last few paragraphs will make clear. It’s about trying to help the literary community as a whole by connecting dots that are as yet unconnected, showing how several recent trends in publishing are converging in a very, very bad way through a natural and largely unintentional process of business evolution.

_

Step One of a Pyramid Scheme

Sell Hope

The first trend in publishing that threatens to undo the industry’s long-term sustainability is the transformation of the role of the writer from talent to just another class of consumer.

Jim at Dystel & Goderich shares this anecdote:

At a writer’s conference a few years back, one of the organizers implored me to, “Keep it happy. No one pays to hear they won’t make it.” Which led to some questions on my part: … is it fair to tell publishing pros to keep it peppy so as not to scare off potential paying guests to your next writers conference?

But, treating writers as just another source of revenue is not limited to writers conferences. The self-publishing biz, now thundering toward full boom with the proliferation of e-book readers and print-on-demand (POD) possibilities, has long targeted writers as consumers.

Even some literary agents are talking about charging writers up-front for “services” like reading their manuscripts. It is painful to read the arguments deployed in defense of this idea, particularly because I sincerely do not believe that the agents deploying them fully understand their insulting and self-cannibalizing implications.

For example, I have read agents defending the idea of charging reading fees on the grounds that “true” professionals do not provide products and services for free. The implication, of course, is that the literary agent is a professional, but the writer is not. After all, isn’t the whole idea behind hiring a literary agent that you would like someone to pay to read your writing? A literary agent who asks the writer to pay to be read has reversed the natural logic of the relationship.

Reversing the direction of consumption not only kicks off the writer-agent relationship on the wrong foot, but it distracts the agent from the larger — and more professionally proper — source of funding: the publisher.*

Most writers’ agents are not able to wrangle publishers into dipping deep enough into their profit margins to enable the writer to quit his or her day job. If most writers have a steady paycheck outside of their relationship with agents, but the agents rely entirely on writers to pay the rent, the last thing agents want to do is alienate writers by treating them like consumers.

No offense to the lit agents out there, but the money you’re looking for is in the other direction, guys. The same direction as the money we’re looking for as writers. The same direction as the money publishers are looking for. The money is in the hands of readers.

If that money is getting siphoned to a trickle before it reaches you… well, there’s your real problem.

~♦~

But, I don’t want to imply that the transformation of writers into consumers is solely internal to the relationship between writers, agents, and publishers. I also have a great big fat finger to point at colleges that rake in tuition money “training” people to be creative writers,** and the undeniably profitable writing advice market.

For example, the profiteering conference organizer Jim quoted above.

Now, I understand that there is a justifiable need for mentoring in any profession; that’s how we develop better professionals as a civilization. However, once the shift is made from an apprenticeship and advice model to an advice consumer model, the field ceases to be about selling the product or service and starts to be about selling the hope of being a seller.

Did you feel a cold shiver when you read “selling the hope of being a seller”? That was the ghost of the Pharaoh Khufu hovering over the future gravestone of the publishing industry, which is in the shape of a pyramid.

And, when what publishing pros are selling is simply the hope of being a writer, then the more buyers the better. Never mind whether they can actually write worth a lick.

Have you ever picked up a book, in the writing section of your favorite bookstore, with a dust jacket that blurbed right in your face something like, “Anyone can be a writer by following these 5 simple steps”? Walk away from the writing section and mosey on over to the business section. I wager that within 30 seconds you can find this: “Anyone can be a successful business leader by following these 5 simple steps!”

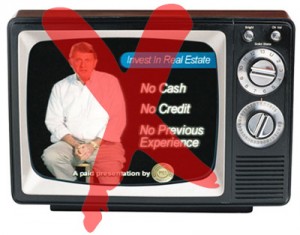

Now go home, relax, have a glass of your favorite beverage, wait until regular programming is over, and turn on the television. See the man with the paid audience? What’s he saying with those shiny shiny teeth? “Anyone can be successful in real estate by following these 5 simple steps!”

What these people are selling is not literature, or business expertise, or real estate. What they are selling is hope — which has a great turnaround, I hear, because it doesn’t take much to produce. It doesn’t even require truth as an emulsifier.

What these people are selling is not literature, or business expertise, or real estate. What they are selling is hope — which has a great turnaround, I hear, because it doesn’t take much to produce. It doesn’t even require truth as an emulsifier.

“No one pays to hear they won’t make it” = “Tell them they’ll make it so they’ll keep paying, whether they have a chance of making it or not.”

This dishonest consumerization of talent is the danger against which those ethical prohibitions about reading fees are intended to protect, however uncomfortable they may be. It’s not that agents as a class can’t be trusted. In fact, it’s not about agents at all, but about human nature and the flaws which we all share.

Because of the way humans are, some ethical slopes are indeed quite slippery, particularly when lubricated by financial necessity.

Of course, there are those who will insist that they would never allow that slippery slope to influence their professional decisions. Also, they drive just fine when they’re drunk. And, they would never talk to their kids like that, if they had kids.

The reality is that the people who put those ethical rules in place were wise enough to understand the risks of treating represented talent as a source of income. It overturns the entire business model and aims it in the wrong direction.

Step Two of a Pyramid Scheme

Each Buyer Becomes A Seller

It has become a standard piece of advice to writers that they should expect to do most, if not all, of the marketing for their book by themselves. Create an online presence, recruit bookstores to carry your book, round up readers, pester the living daylights out of your local lit-minded media. Sell, sell, sell!

Why? Because publishers can no longer be bothered to market your book. They will tell you that they have a very narrow set of “lead titles” to focus on, and not a dime can be spared for yours. And, this isn’t something to complain or be “bitter” about, unless you want to be branded naïve or unprofessional. It’s just the way things are, say the Powers That Be. Deal with it or don’t.

[Side note: I have read in several places that most lead titles sink like rocks. This may or may not be true, but in light of this I sometimes wonder if I am pronouncing “lead” correctly.]

Funny thing about the ever-tightening marketing focus of publishers: the tighter that “traditional” publishers focus on fewer and fewer lead titles, and the more marketing they shove off onto the remaining majority of their authors, the more they resemble self-publishing services, particularly as e-books and POD take on an expanding role in the market.

In fact, I hereby predict and prophecy (marketh ye my words!) that we will eventually see self-publishing services begin to showcase what they consider promising lead titles, bringing “traditional” publishing and self-publishing together >SNAP!< like magnets.

This would be a terrible eventuality, because it would signal the full-blown transformation of publishing into a giant pyramid scheme stumbling forward toward the inevitable implosion that is the doom of all pyramid schemes.

How so? Well, we already established that writers are being treated more and more like consumers rather than suppliers of talent. And, we’re not only talking about aspiring writers. With most published authors not compensated enough to quit their day jobs, I would really be intrigued to see some hard numbers comparing the average time a writer puts into writing/promoting a novel vs. the monetary returns.

Are all but the best-selling writers essentially giving away their books for free? Or, at least, well below minimum wage income? I would not be surprised to find that they were. If many authors are thus effectively paying publishers in writing time and promotion time, how is this different from self-publishing?

~◊~

But, getting back to the central argument: what makes this a pyramid scheme is the inspiration to write.

Ask most writers what inspired them to write and they’ll tell you it was something they read. Every person a writer convinces to buy and read a book is a potential consumer of the same offer that publishers made to the original writer:

Ask most writers what inspired them to write and they’ll tell you it was something they read. Every person a writer convinces to buy and read a book is a potential consumer of the same offer that publishers made to the original writer:

“If you become a writer, you could make it big. All you have to do is buy these books on how to write, pay to attend these writers conferences, and do your own marketing so that X number of people buy your book.”

And the readers of those second-hand reader-writers? Why, they can become writers too! If they buy this book with 5 simple steps and they gather X number of people to buy their book. And those third-hand readers can then go on to become writers… and so on… and so on…

Eventually you end up with a huge roiling pyramid of writer-readers who are essentially funneling their time and money to the the benefit of passive investors who do quite well for themselves on publishers’ profit margins.

Voilà! Pyramid scheme.

No The Way Out

It is clear that the publishing biz is on the verge of eating itself alive. It may do so in fits and starts, like the Lord of the Nazgûl collapsing into nothingness — crunch by crunch — after Éowyn stabbed him in the face. Each momentary pause in the collapse could be mistaken for rock-bottom, the opportunity for a recovery …

But, until the sustainable, author-driven business model of publishing is rebuilt, re-established, and re-fortified against erosion, fatal instability will continue to squeeze publishing in on itself.

Heed this: if publishing continues to devolve into a room in which publishers play Serrano, agents Garcin, and consumers Rigault, with authors relegated to a nearly line-less Valet slipping in here and there to give the others their places… well, it will be Hell.

And, it will fail. As do all pyramid schemes. You cannot sell the false hope of success to a class of consumers who are expected to recruit new consumers for that same false hope. This isn’t negativity or nay-saying on my part. It’s just an economic reality. I’m merely connecting the dots that others have drawn.

There is a way out. One cornerstone I mentioned a few days ago: publishers could print fewer, better books (with fewer remainders) simply by compensating writers more fairly.

As a writer, I readily recognize how sacrificing a few points of my take to give my agent a 33 percent raise (from 15 to 20 points) could vastly increase my fortunes. Publishers should heed the same logic with regard to writers. A small sacrifice in publisher profit margins could make a huge difference in the lives and loyalties and productivity of writers. And this huge difference in the lives and loyalties and productivity of writers would surely lead to publishers recouping that small sacrifice, and then some.

Secondly, publishers should learn from the “50 State Strategy” of politics, the idea that the way to win national elections is not to focus on swing states, but to invest resources across the entire country. The 50-State Strategy doesn’t mean that you never give up on an un-winnable state/book. It means that you start by marketing everywhere, and cull the un-winnable, rather than starting out by putting all of your marketing eggs into a tiny “lead title” basket.

More importantly, stop forcing writers to do something (marketing) which is utterly orthogonal to the skill-set of a writer. Let marketers market. Let writers write. You’ll get more effective product in both functions. It’s called “comparative advantage” and not only did Ricardo explain it in the early 19th century, Adam Smith mentioned the idea in Wealth of Nations.

If publishers can’t adjust to 17th century economics, there’s no hope of them surviving the late 20th century tech revolution.

And, those who feel that the current lead-title model is the best path to sure profit should remember: we think of the ocean as deep but in reality its massive volume derives primarily from being wide. Relative to its breadth, the ocean is very shallow. In the same way, a broad and shallow marketing strategy can ultimately out-compete a narrow and deep one for volume, even if it doesn’t produce spectacular best-seller successes.

Thirdly, not only do agents around the world need to re-affirm their commitment to the ethical rules of their various associations, but agents and publishers need to come together to establish a common set of standards for vetting literary work, which can be prominently branded as a seal of excellence separating professionally reviewed, quality fiction from … well … from the unwashed masses of self-publishing.

And, before anyone gets all offended and butt-hurt, let me remind all that I am currently among those unwashed masses. I may even decide to self-publish, outside of that seal of excellence. Therefore, I might ultimately suffer from the proposal I am advocating here, but I still believe it is in the best interest of the lit biz as a whole, and therefore in the best interest of civilization.

But, to continue on the current path, consumerizing writers and pushing them to recruit more readers, who become the next writer-consumers … this business model is ultimately a sham, a confidence game, a racket, and publishing industry pros need realize this if they want to save their profession over the long term.

_

_

* Also, if I were willing to pay someone to read my novel, I would just go ahead and pay someone to print up a bunch of copies too, rather than going through an agent.

** I was in such a program before switching colleges and majors, so I’m allowed.