There’s a whole lotta “self” going on in publishing, from the web-driven growth of self-publishing to the expectation of author self-promotion in traditional publishing.

There’s a whole lotta “self” going on in publishing, from the web-driven growth of self-publishing to the expectation of author self-promotion in traditional publishing.

Many publishing professionals — writers, agents, editors, critics, etc. — are trying to ride this wave with a sewn-on happy face, afraid that expressing skepticism equates to missing the boat or swimming against the tide.

Take a lesson from the real-world referents of these watery metaphors: some waves you ride, but some waves you build walls against. Author self-publishing and self-promotion together constitute a destructive wave that merits a levee, not a longboard.

The Saruman Defense

When discussing many of these trends in publishing, people often make a fatalistic appeal to the irresistible power of the “revolution” while encouraging others to join it. The argument is often framed in very inspiring and progressive-sounding language, but it still boils down to the inescapably Orwellian logic of “Surrender is Victory!”

"We cannot resist this new Power. We must join It!"

It is essentially the same argument Saruman made when trying to convince Gandalf to join with The Enemy. Or, less literarily (and less charitably) it is the policy of Quisling in World War II.

Getting back to our wave metaphor, a similar argument would be that hurricanes are powerful, so we might as well destroy New Orleans. When I hear people trying to ride this surge, it sounds to me like: “Real winners (like me!) learn to love the Storm; I wag my accusatory fingers at people who fail to survive it! Don’t be weak and backward like them!”

If only everyone cheering on this maelstrom would instead grab a shovel and start filling sandbags…

Now, before someone thinks that those who have made a successful go of self-publishing and self-promotion provide some sort of counter-evidence: I am not saying that it’s impossible to ride a destructive wave. I’m just saying that even if you manage to ride a destructive wave, it still dumps you into a soaked and scattered wasteland where once had been a thriving city.

What’s the point of being named best surfer in a toxic disaster zone?

Tomorrow Could Be Another Day

Those who are scrambling to snap heels and salute this bad turn in publishing would argue that they are merely “facing reality.” But this self-promotion trend is only an accidental reality in publishing, an epiphenomenon floating on the surface of social currents that are swirling as people come to terms with very recent technological and economic developments.

We still have a choice how we come to terms with those developments. Not only is the easy road of surrender not the only road, but the easy road does not address all of reality, merely the surface of it.

There is a deeper reality to contend with, hardwired into human psychology, which spells big trouble for an industry indulging a fad that rewards self-promoting enthusiasm over the professionally vetted value of product. This deeper reality is that the writer is the last person who should be deciding whether and how much a book should be promoted for reading, because self-promoting enthusiasm and value are at odds with each other.

A real-world example: Margaret Mitchell was hesitant about showing Gone With The Wind to publishing professionals, only doing so after being specifically asked for a manuscript by an editor, turning him down, then handing it over on a rash impulse after getting angry about an overheard comment by a snarky co-worker. And, even after Mitchell had submitted it, she tried to retract the submission. The publishing professional to whom she had given it, however, recognized its merit and convinced her to have it published.

The rest is history, as they say, but let me remind you of it. Gone With The Wind won the 1937 Pulitzer. Its film adaptation won 10 Academy Awards. It has inspired a sequel, an ironic alternate telling, and four musical stage plays, not to mention popular references too many to count.

The lesson here is that the best (and most profitable) writers are often not merely bad self-promoters. Often they simply are not self-promoters at all. That’s why the traditional model of publishing included professional promoters, employed by the publisher, to encourage writers and reach readers. In fact, traditional publishing still employs such promoters for their “lead titles.”

Long story short: there is a right way to do things, a sustainable way to do things, and its vestiges are still embedded in the professional memory of the publishing biz. Its professionals simply need to have faith in it again.

Gone With The Hot Air

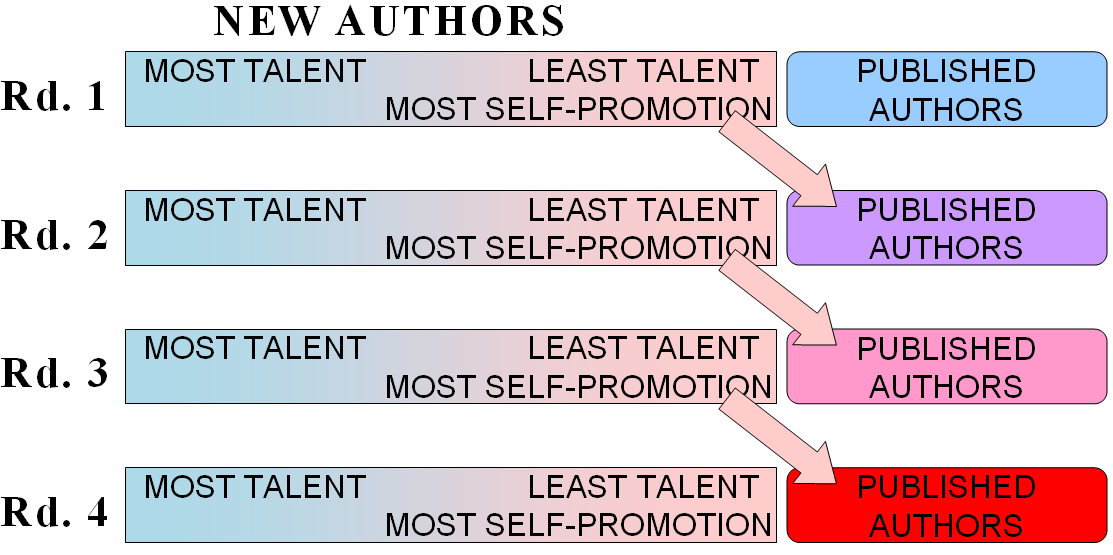

If it is true that the best writers are often not self-promoters, the opposite is also true: the best self-promoters will tend to be bad writers. And, there is clinical research to support this in the infamous Dunning-Kruger Effect.

For those not familiar with the research of David Dunning and Justin Kruger, the conclusions of their research basically boil down to two observations:

- Those with the least ability in a particular skill tend to have an inflated estimation of their ability.

- Those with the most ability in a particular skill tend to have a deflated estimation of their ability.

Now, apply these two observations to a hypothetical group of writers selected at random and take a guess who will be most enthusiastic about promoting his or her book.

Now guess into which category tomorrow’s potential mega-blockbuster debut author like Mitchell would fall.

Now guess how much reader face-time that potential mega-blockbuster debut author is going to get with a million self-promoting hacks and mid-listers shoving their books in readers’ faces.

Now guess what this means for the long-term sustainability of a business model based on author self-promotion while publishers focus marketing efforts on a tiny field of lead titles by already famous names.

At least, Dunning and Kruger found, when provided with evidence of their high position on the spectrum of performance, competent people are then able to accurately judge the excellence of their skills. Like Mitchell, they can accept external assessments and stop hiding their light under a basket.

(This attentiveness to the world outside is, I believe, part of what makes competent people competent in the first place. But, this is beside the point.)

Incompetent people, however, continue to overestimate themselves even when faced with concrete proof of their incompetence. They cannot be deterred by facts, only by outright denial.

What this means for publishing is that bad writers, if not quarantined by a vigilant and selective class of insightful gate-keeping professionals, will simply keep multiplying and shoving their bad and mediocre books in the faces of a public which, as a consequence, will suffer ever-dwindling expectations of value and thus an ever-dwindling willingness to pay, until the whole industry becomes the literary equivalent of a food fight with everyone throwing and nobody eating.

And, nobody paying.

Profit is Profit, Right?

Some might object that, even assuming that science is real and my wet blanket analysis is sound, so long as some mediocre self-promoting writers are still making money, publishing as a whole can survive, right?

Wrong. The problem is that moderate individual success does not always promote community success, because each transaction sets the stage for the next. Community success is not merely the sum of individual successes, it is a complex dynamic of interactions wherein one person’s success now can undercut another person’s later.

Time spent reading a mediocre book that leaves the reader unenthusiastic about books for a while (or worse, convinces them that they could also easily become a published author) is time not spent reading a masterpiece that commands both respect and a higher price.

If a million eager self-promoters are each making 100 bucks in profit by drowning out a thousand literary wallflowers, that’s nowhere near as healthy as an industry where a thousand literary wallflowers make 100 grand in profit because their writing is simply better in quality.

Yes, math nerds, those numbers add up the same … for a single business cycle. The consumers’ respect for the product, however, does not add up the same, and this has consequences for future cycles. Esteem for the product drives consumers’ willingness to pay over time, particularly when that product is an optional buy with much cheaper or free alternatives.

Just ask anyone who sells luxury purses.

If people think less of your product, they will be less willing to pay much for it. If they think more of it, they’ll pay more … even if it costs the same to put on the shelf. But, unlike with luxury purses (which are often indistinguishable from their knock-offs) you can’t fake literary quality.

Now factor in the additional psychological reality that people are less likely to believe self-promotion than they are promotion from someone other than the person being promoted. Imagine showing someone a résumé with three letters of recommendation … all written by yourself. It would be laughable. The same applies to book promotion. There’s a huge gulf in credibility between “my book is awesome!” and “we found this author whose book we think is awesome!”

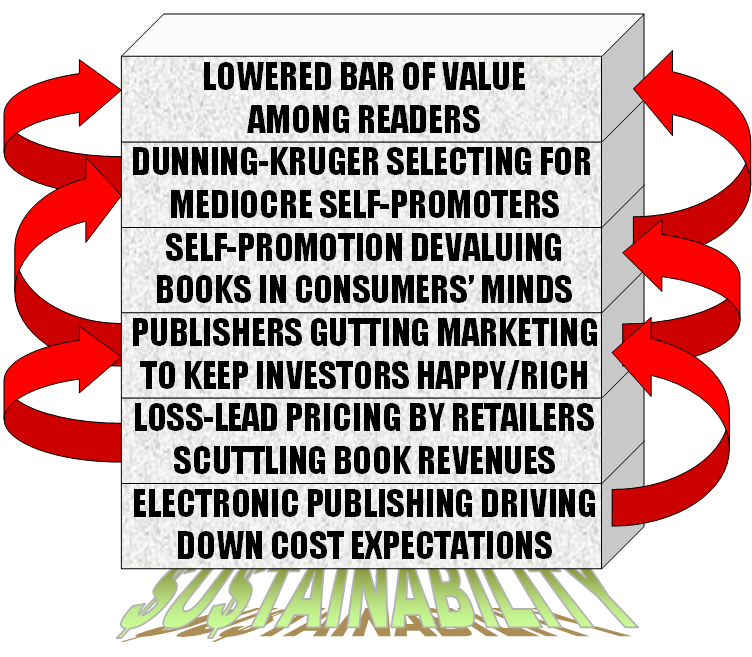

Reiterated effect of the Self-Promotion model given Dunning-Kruger selection.

So self-promotion, even before factoring in the Dunning-Kruger effect, devalues the product in the mind of the consumer, helping suppress prices over time.

So, yes, publishers can abandon marketing to the most self-promoting authors on their lists, they can refuse to get together and crank up their professional standards to distinguish their common brand of “traditional publishing” from the anarchy of self-publishing, and the industry can stay afloat.

Temporarily.

But reader expectations of quality will dwindle, dragging prices down with them, which in turn cuts into vetting and marketing resources, in a vicious cycle that points the business bottom line straight toward zero.

_

* Unfortunately, even in choosing lead titles, publishers often select crappy writing that comes with the self-promotion inherent in a famous name. *cough* Glenn Beck *cough* The fact that The Overton Window was a best-seller, however, doesn’t change the fact that its substandard writing affected readers’ estimation of fiction in general, and therefore what they feel they should pay for it … if anything.

Les Edgerton

July 21, 2010 at 8:56 am

Brilliant post once again, John. I hope traditional publishers see this and take note. You are proof that there are still people using their gray matter…

Flannery O’Connor saw this a long time ago, when asked by an interviewer if university writing programs discouraged writers, to which she replied, “Not enough of them.”

As I noted in a recent post, I wonder how many people would be submitting if they had to pay the costs in money, time and energy of yesteryear when all that was available was snail mail. For all the ills of the post office, at least they kept a lot of bad writing from even being sent in to publishers or agents. The same thing applies if electronic publishing cost as much as traditional publishing.

There’s a writer whom I won’t name who gets a lot of press about how much he/she makes with e-sales. What isn’t noted is that this writer was extremely fortunate to have his/her books published by a traditional press, as they are truly awful. Mediocre at best. When his print books didn’t sell all that well at print prices, he went to e-publishing and is making boatloads of money. Why? Because they became available at their true value, $1.99. They were never worth eight or nine bucks for paperback and certainly never worth hardcover prices. The wonder isn’t that he or she is selling lots of books for a couple of bucks, but that he was ever published by a traditional publisher. This part of the story is never told.

We need more truth as you give it, in this business, and less pie in the sky. Perhaps less vampires as well…

J. Nelson Leith

July 21, 2010 at 10:09 am

Les, glad you liked it.

I was joking to myself as a clicked the publish button that maybe I should title this series “Burning Bridges” rather than “My Two Cents,” so it’s encouraging to know that someone out there appreciates arguments for the common good.

Les Edgerton

July 21, 2010 at 10:29 am

I know what you mean. There will always be somebody who will take it the wrong way. Nobody is trying to discourage good writers who have talent and work hard… but those aren’t the folks who will take offense.

It’s like the “writer” I mentioned. He’s a nice guy and we’ve met, but his work is truly mediocre at best. His books are basically a “gimmick a go-go.” I don’t want to embarrass him (not sure if that’s possible, actually…) but so many people cite his “success” and don’t know the whole story. I really doubt that if he hadn’t been published in print (and continues to be so) that he would have come close to the e-success he’s enjoyed. There’s a reason he never made more than $20,000 in sales from his print work. At $1.99, it’s an entirely different story and one unlikely to be achieved by a total unknown. It’ll happen, but then lightening hitting the same person at 4:30 on two Thursdays in a row will happen also, but it’s not something to bank a writing career on…

Nathan Bransford has some interesting stuff on his blog about this also. He sees the Internet as becoming the new slush pile…

I see this perhaps as shaking out kind of like the movie industry. The studios keep making the same movie over and over again and then an indie will take a chance and have a hit or series of hits and the paradigm shifts. Then, the indie becomes a major studio and begins putting out the same product, and a new indie shows up… ad nauseum. What I see are smaller, niche publishers having success by going against the flow and getting bigger and becoming establishment and on and on. But, I don’t see print going away.

Part of the problem is that editors at traditional houses are running scared and that makes agents react accordingly. Someone prominent in Hollywood a couple of weeks ago said, “Nobody’s looking for bestselling novels to make movies from these days–we’re only looking at mega-bestsellers. Since Hollywood drives the publishing business to a great extent these days, we’re seeing the same mentality apply to print. But, this too, shall pass. Hopefully…

Scott Nicholson

July 21, 2010 at 12:10 pm

Interesting, and I appreciate your upstream take on the digital phenomenon, but you are assuming Margaret Mitchell would even be published today. Most agents would be asking where the shagging vampires were.

Since when has literary quality ever been a prime motive for the average reader? How many of us sneaked our “real favorites” into class when they were trying to make us read Moby Dick and James Joyce for our own good? Sorry, in this age, the great self-promoter will kill the great writer

every.single.time.

The only chance is if book bloggers truly take on the role of finding great and worthy works instead of just mumbling some company line about how great the latest bestseller is.

Either way, I don’t think literature is any danger. It finally belongs to the readers, and I quite think they can be trusted more than anyone else. Thanks for the post.

Scott Nicholson

http://hauntedcomputer.blogspot.com

tbrookside

July 21, 2010 at 1:59 pm

“The problem is that moderate individual success does not always promote community success…”

I’m sorry, but – So what?

That’s really the question that has to be asked here.

Let’s say that the Dunning-Kruger effect applies to me. Why should I care? In fact, why wouldn’t that make me even more determined to self-publish?

If I actually have no talent, then I could never be published any other way. So my available choices are self-publish and self-promote my way into some modest number of readers and some modest amount of money, or – zero. Zip. No readers, no money. That seems like a pretty easy choice to me.

If you want to convince people not to self-publish and self-promote, you’re going about it in exactly the wrong way. You should tell people they’re geniuses and if they just wait a little longer and try a little harder they’ll get traditionally published and be the next Stephen King. That may be completely untrue, but it is at least an internally logical reason to not self-publish. “You suck, and you’re too incompetent to even know it!” is not. In fact, it’s the reverse.

Les Edgerton

July 21, 2010 at 2:06 pm

The thing that makes that premise wrong is that self-publishing isn’t publishing. It’s vanity printing.

tbrookside

July 21, 2010 at 2:34 pm

Who cares?

A completed manuscript is an asset.

That asset can achieve a dollar value in two different ways: someone can publish it for you, or you can publish it yourself.

If I’m a no-talent idiot, no one will publish it for me. Right? They’ll just throw it away and send me rejection letters. So that makes the value of the asset if I make that choice $0.

If I’m a no-talent idiot but I self-publish the book at Amazon anyway, somebody will buy it. Maybe not a lot of people, but the number is higher than 0. That makes the value of the asset something >$0 if I self-publish.

“But that’s just vanity printing!” But what difference does that make? If something better were available, it might make a difference. But if I stink, nothing better is available and as a result there’s no downside. Right?

That’s why I’m saying that your best bet is to tell all slushpile writers to just hang in there and wait for their big break. You might rope some of them in with hope. And you need to use hope because you can’t use fear. Since they are already at 0, there’s really no way to present them with anything to fear.

Les Edgerton

July 21, 2010 at 2:49 pm

I’m sorry, but a completed manuscript isn’t an asset at all. A published manuscript is an asset. An unpublished mss or one that was self-published is only a pile of typing.

A self-published writer isn’t a writer. He’s a typist. Perhaps a typist with money to pay to get his stuff printed, whether it’s an ebook or a printed book. There’s absolutely no value in the least in that.

I have no problem with someone who wants to do that, but just don’t call it what it isn’t. And what it isn’t is writing. Or publishing. It’s typing. And probably why no one would publish it and pay reasonable money for it. It doesn’t have any real value.

Also, if a person self-publishes or vanity publishes (hate that term as it’s incorrect–it isn’t publishing but printing) that’s their business, but if they ever want to get published legitimately, I’d advise not to mention they’d self-published. That would just about doom their chances with any real press.

Self-publishing may do something for a certain type of person’s ego, but that’s the type of person who wants all the kids on the baseball team to get a trophy. And not keep score…

J. Nelson Leith

July 21, 2010 at 3:06 pm

Worse than just a pile of typing, Les, I would say that an unpublished manuscript is an investment, considering the time and energy that (one would hope) was put into it. At the point of querying, the writer/typist is deep in the hole, economically speaking in terms of the opportunity cost, something that both crappy writers and stingy publishers should both bear in mind.

Even if a bad writer makes a little bit of money through a vanity press, whether he/she recoups the investment of writing and marketing is another matter entirely. I would suspect that most “self-published” authors (and a lot of genuinely published authors) end up deep in the red as an economist would measure it, even if their accountant tells them they made a profit.

tbrookside

July 21, 2010 at 3:11 pm

Every product at Amazon with a sales rank has sold at least once.

The minimum amount the sale of a self-published kindle title at Amazon can net the author is 35 cents.

That means that every self-published e-book at Amazon with a sales rank has, or had, a minimum value of 35 cents.

I’m not sure how we can argue that an item with a sales history has no value.

Self-publishing may do something for a certain type of person’s ego, but that’s the type of person who wants all the kids on the baseball team to get a trophy. And not keep score…

But the decision tree is the same if you engage it completely in the absence of ego.

If you don’t care – absolutely don’t care – if you’re good or bad or if anyone thinks you’re good or bad, and you have a completed manuscript, game theory says you should self-publish it at Amazon. It produces the least-worst outcome across the widest possible range of “attempts”. This is especially true if, as you argue, the Dunning-Kruger effect makes it impossible for us to evaluate our own abilities. If most system participants stink and don’t know it, we should make our decisions assuming that we stink, too.

If you’re right and the terrible scenarios above will come to pass, then it’s even more imperative that you self-publish as quickly as possible – because we have a Tragedy of the Commons situation underway and the clock is ticking on the exhaustion of the commons.

J. Nelson Leith

July 21, 2010 at 3:20 pm

A book with a single sale on Amazon does not have a value of 35 cents, not in economic terms, because the book didn’t just magically poof into existence. It represents an investment of time and energy, which has to be recouped before it begins to have positive value.

tbrookside

July 21, 2010 at 3:24 pm

At the moment when you are making the decision to publish the manuscript, or not, the time and energy are a sunk cost.

Even if you never recoup that cost, that doesn’t have any impact on the decision regarding whether or not to publish that manuscript. With the manuscript in hand, any action that leads to revenue, however meagre, is better for the author that any action that leads to no revenue.

J. Nelson Leith

July 21, 2010 at 3:27 pm

I would also like to clarify (if the post itself isn’t clear) that this argument was not intended to dissuade the bad writer. I specifically note that incompetent people aren’t swayed by evidence, anyway, something that trying to argue with one of them makes clear.

The word I used to describe what should happen to bad writers is “quarantine,” and that’s a call for action directed at publishing professionals, who are the intended audience.

J. Nelson Leith

July 21, 2010 at 3:34 pm

Now you’re simply arbitrarily setting the clock to suit your desired outcome. But, it still doesn’t support your conclusion.

In order to have a “manuscript in hand” you have to first make a decision to write, at which point that time and energy are not sunk costs.

But, even with manuscript in hand, self-promotional efforts are still in the future, making the sunk cost argument again invalid.

Les Edgerton

July 21, 2010 at 3:42 pm

If a self-published book sold for 35 cents on Amazon, technically, yes, it has a value, but nothing that anyone with any sense would consider of value. Nothing has been validated. No one with any knowledge has vetted the product.

Self-published typists remind me of a baseball player with no talent showing up at a SF Giants tryout and getting laughed off the field and so, with his Walter Mitty mind, buys a uniform and gets eight other dweebs together and calls his product a baseball team. He may even rent a field and play a game and somebody may pay a buck to attend, so technically he’s a “professional ballplayer.” In his mind only. In the eyes of anyone who knows the game, he’s a… dweeb who can afford a uniform and rent for a field. Don’t see much difference in that and self-publishing and selling fifty copies of his typing.

I think the problem is there’s a mindset in this country that people are “entitled” to things. Sorry. You’re entitled to try but not entitled to make the Yankees. Or get published. Or have someone support you. (Although, that looks as if it’s changing…)

If a traditionally-published book doesn’t make money, that’s only part of the equation. The fact that a qualified person (editor) saw enough value in it to publish it is important validation. These people have a recognized acumen. They aren’t just Joe Blow or Jane Blow off the street. They possess a certain level of accepted knowledge and judgment. Do they make mistakes? Sure. Who doesn’t? The guy who works on the line at Ford puts out a bad part occasionally, even if he’s the best in the company. Does that mean his judgment isn’t any good? Not at all.

If a person doesn’t care if they’re good or bad or if anyone with any chops thinks they’re good or bad, and they have a completed mss, go ahead and place it on Amazon. Nobody will give it any respect. It’s your imitation of a Pet Rock.

I don’t believe anyone takes the Dunning-Kruger effect completely seriously–it’s given with a grain of salt. Obviously, there are people who know their work is of quality. What is perhaps more likely is that there are many people who don’t know their work isn’t any good. That’s the vanity press market.

If a person thinks that having a physical book in their hand with their name on it is the mark of an author, it is if an independent and legitimate authority deemed it so (an editor/publisher), but if it was self-published the only authority that determined its worth sleeps in the same bed with the writer and sees the same face in the mirror every morning.

And isn’t worth all the time we’re spending talking about it!

Ciao!

tbrookside

July 21, 2010 at 4:50 pm

Self-published typists remind me of a baseball player with no talent showing up at a SF Giants tryout and getting laughed off the field and so, with his Walter Mitty mind, buys a uniform and gets eight other dweebs together and calls his product a baseball team. He may even rent a field and play a game and somebody may pay a buck to attend, so technically he’s a “professional ballplayer.” In his mind only.

Actually, by the only real definition, as soon as anyone pays a buck to attend, that’s absolutely what they are: professionals.

A professional is someone who performs work for pay. The difference between an amateur and a professional is the first dollar earned. [Or the first 35 cents.]

You’re trying to argue that there is some additional, ineffable quality that defines a professional, and you still haven’t adequately defined what that IS.

Let’s say the field was free and the uniforms were free. You can take the free field and the free uniforms and people will pay you to play baseball. Baseball is fun for you, and you enjoy it – and if you just pick up the free uniforms and go out on to the free field, people will pay you to watch. If under those circumstances you refrain from going out on the field because you aren’t as good as Derek Jeter, you would be an idiot. Some would say a coward as well. Turning down money for playing baseball because you’re embarrassed you might not be as good as Derek Jeter? What are we, children afraid to raise our hand in class? Teenagers afraid to ask a girl out?

Les Edgerton

July 21, 2010 at 5:25 pm

This sounds like Bill Clinton trying to use semantics to prove he wasn’t immoral. Worked for some, I guess…

Nobody argues the dictionary definition of a “professional.” Of course, the real-life definition is a bit different.

Also, I don’t feel I’m trying to argue there is some additional quality besides being paid for work that defines a writer. It’s crystal-clear what defines a writer. Getting published. Self-publishing and vanity publishing isn’t publishing no matter how many times someone insists it is. I don’t see very many published writers saying it is. Wonder why?

And I wasn’t talking about how the no-talent baseball player who claimed he was a professional because someone paid a buck (or thirty-five cents) felt. Who cares how he felt? He doesn’t count, at least in a baseball discussion. Nor do self-published or vanity press typists count in discussions about writing. It just isn’t.

I’m going to leave this. When words like “moron” and “coward” and “idiot” begin turning up in a debate, I sense a non-published and frustrated typist at work–one who has to resort to trotting out those kinds of words to make some kind of Mickey Mouse argument. Sorry. Gotta go and write. Work that’s publishable…

It’s difficult to follow a circular argument that is mostly specious…

Sorry, John. Didn’t mean to go on so long with this. I loved your post.