Discussing her twist on Bram Stoker, titled Dracula in Love

Discussing her twist on Bram Stoker, titled Dracula in Love, author Karen Essex wrestles with the slippery definition of the “literary” … and its many pretenders.

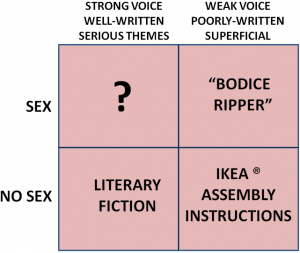

Her piece at Publisher’s Weekly, “No Sex, Please, We’re Literary,” got me thinking about the way we categorize literature, and how it holds us back from really understanding — and enjoying — the stuff we read.

Essex confesses to having…

tortuous debates over just how much sex would be too much. My most trusted readers are my agent, my editor, and my manager (yes, I’m lucky), and each had very different responses. Without giving away proclivities, two on the team kept begging for more, though what one thought erotic, the other sometimes found terrifying. The third loved every sensual drop, but kept reminding us of the puritanical level of the basic American reader, specifically, the literary reader, that elite creature who relies on a host of signifiers to be distinguished from the genre reader. She pointed out that the book had the elements that discriminating readers look for in a literary work: a strong, authoritative voice, painstakingly composed prose, and serious themes. “This book is too rich to have its seriousness dismissed because of the sex scenes,” our cautionary voice reminded us. “You know how readers are! They see some sex on the page and assume it’s a bodice-ripper.”

At first, I was tempted to reply, “Do they really?” but, yes, they do. And they do this because we have a very confused system of classifying literature, with definitions that clumsily draw lines at cross-purposes to each other.

For example, what does the presence of sex have to do with the absence of voice, well-written prose, and serious themes? Nothing at all. (And, this from a writer who rarely depicts sex in his writing.) So, why should readers dismiss the literary potential of a novel with sex scenes?

For example, what does the presence of sex have to do with the absence of voice, well-written prose, and serious themes? Nothing at all. (And, this from a writer who rarely depicts sex in his writing.) So, why should readers dismiss the literary potential of a novel with sex scenes?

The bizarre conventions with which we saddle ourselves, writers and readers alike, need to be refined.

For example, the fact that most novels in “high fantasy” settings were, at some formative period in literature, primarily adventure stories does not change the fact that a magical Medieval world is a type of setting while adventure is a type of plot.

So, recognizing that “romance” is a type of plot largely independent of what sort of world the lovers inhabit, what would we call a romance set in a land of swords and sorcery? Does plot trump setting, making it a romance, while an action adventure novel in the same setting would be called fantasy?

What about an adventure set in 1930s Borneo rather than The Elvenwood? Oops! Now, setting trumps plot? And, what about a 1930s Borneo with elements not from real life, but scientifically plausible? Science fiction or adventure? What if we throw some magic in there instead?

Yeah, I know the categories don't make sense; that's kinda the point.

What are the rules here? (Hint: there are no real rules here.)

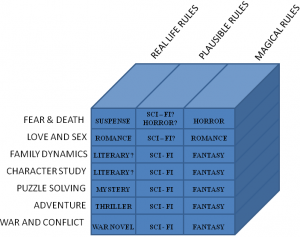

So, let’s agree that setting, realism, and plot theme are separate issues. For example, imagine a grid with some common themes down the side and the level of realism along the top.

A scary story with a magical villain is “horror” while a scary story with a realistic villain is “suspense”? Why do we make that distinction? Or, do we always make that distinction?

And what about a scary novel with an unreal, but scientifically plausible villain? Would that still be horror? Would it only be sci-fi if the villain is a drooling alien hunting the crew of a spaceship in the far future? Does the innovative application of a real-life air gun to blast away doorknobs count as science fiction?

Back in the Game

How could we make this taxonomy more realistic? We could insist on a genus-species model, with the “real life” versions of each theme standing as the default, without qualification.

Then we have “fantasy suspense” for what has been called “horror” alongside “sci-fi suspense” and just plain old “suspense.” We also get: romance, sci-fi romance, and fantasy romance; mystery, sci-fi mystery, and fantasy mystery; adventure, sci-fi adventure, and fantasy adventure…

Do some of these sound familiar? We already occasionally use a few of them, when taking care to describe a novel that falls into an established theme outside of the norm for its style of realism.

At this point, scanning the graphic above, some might protest:

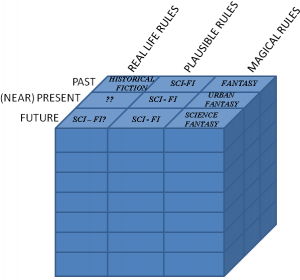

But, Mr. Leith … Dude Sir … what about “historical fiction” which obeys real-life rules, but is still categorized separately? And what about “space opera” which is technically fantasy but more akin to science fiction in its setting and accoutrements?

Huh, I guess the grid we worked out up there really doesn’t cover it all, does it?

Huh, I guess the grid we worked out up there really doesn’t cover it all, does it?

So let’s imagine a grid with the same range of realism along the top, but down the side we have future, past, and present — or nearly present. We don’t want to miscategorize stories because they happen a few decades ago or in the near future.

Here we see “historical fiction” pop up, and “urban fantasy,” with “science fantasy” as a more dignified moniker for “space opera.”

But, where does the “western” fit in? Is it really just a form of historical fiction? I say: “Yes!” Despite its specific conventions, it is still a form of historical fiction. Just like Patrick O’Brian’s novels. Just like World War II novels. Every setting has its specific conventions.

And, is any story set in the future necessarily science fiction, even if we don’t introduce any new creatures or technology? For example, I’m thinking George Stewart’s Earth Abides, even though some might protest that the disease that kicks off the story — even though it may just be a powerful strain of measles — qualifies as a new, sci-fi creature.

Perhaps, perhaps not. But, everything that happens afterward, while speculative, does not expand upon the known phenomena of science. It’s just a story about people in a fictional but realistic situation, like pretty much any other story that follows real-life rules. Why is this science fiction?

No FedEx plane ever crashed in the South Pacific, stranding a systems engineer in a setting just as primitive as in Earth Abides, so is the Tom Hanks film Cast Away also science fiction because it presents a future scenario based on a scientifically plausible disaster?

Back to the Original Question

Okay, so I’m not seriously proposing we reclassify the entire literary world. I just want to demonstrate how simplistic and arbitrary our current categories can be.

Getting back to the original question, we have uncovered all sorts of nonsensical distinctions without even addressing the issue of merit. And, having created a solid cube of literary possibility, in order to add another dimension to measure the continuum from hack writing to literary fiction (let’s call it the Picoult-Franzen spectrum) we would have to bend our minds to the tesseract.

So, to avoid long-term psychological damage, let’s just say that I don’t believe that Karen Essex’s novel should be excluded from the literary even if it qualifies solidly as a romance. The whole genre-literary distinction is nonsense. The twin considerations of genre and literariness do not lie along the same spectrum, except to those trapped in the most one-dimensional order of thinking. They are, in fact, perpendicular to each other.

Genre is the literary equivalent of dialect. Everyone has an accent, and the idea that some people don’t have an accent because they speak “proper” English is just a silly and uneducated prejudice. Likewise, every story has a genre, and the idea that some stories aren’t genre because they are “literary” writing is just a silly and miseducated prejudice.

The literary can be found in any plot theme, in any setting, even romance or science fiction or fantasy or Old West historical fiction. It has nothing to do with who or what you’re writing about and everything to do with why and how well you’re writing.

We need to get over the stumbling blocks that keep us from seeing this clearly. For example, mountains of trouble arise from the fact that certain “literary” subjects like family dynamics and character / personal growth stories are assumed to be written only in realistic settings. Even when the author tosses in some quasi-magical elements (as Toni Morrison often does) we shrink from tagging it “fantasy.” Why?

Some might object to lumping Morrison in with, say, the typical Elvenwood or loveable vampire fantasy. But, there are crap stories about families and social injustice that contain no magical elements at all. Why is it okay to lump Morrison in with sub-par fiction of the same plot theme but not with sub-par fiction of the same ruleset?

Simple literary prejudice. Which is ironic, considering that prejudice is a recurring theme in Morrison’s fiction.

Others might protest that Morrison’s magical elements are metaphors with a deeper hidden meaning, and therefore do not qualify as “fantasy.” Because, you know, the supernatural events in other fantasy stories are never metaphorical.

Dracula’s not a symbol of anything, right Karen?

Back to Basics

So, let’s just collectively cut it out.

First, as readers, try to get a grip on what we really like to read, and why. Are we really “science fiction” fans, or do we find ourselves reading mostly about inter-galactic conflict, with the occasional Civil War or knights-in-armor novel thrown in? Do we like a good mystery even if the “detective” is a member of the Prætorian guard?

Getting a better idea of why we read can keep us from making unfair and unrealistic judgments, and robbing ourselves of a lot of reading enjoyment in the process. Don’t get tripped up by bad categories.

But, publishing pros have a role to play, too. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve highlighted an entry in Writer’s Market with my Nope-colored marker because the “needs” section featured a genre either so absurdly specific (“rural ethnic paranormal political thriller”) or so indecipherable (“nascency fiction”) that it made my head hurt.

Let’s just take a deep breath. At a certain point we have to realize that we’re counting how many genres can dance on the head of a pin. We need to get back to basics.

Here’s one place where I can agree with the gripes of authors like Picoult and Weiner: when they complain that writing by women gets pigeon-holed as “chick lit,” I concur even if they do write primarily for women readers. Personally, I don’t think it matters that there are easily identified conventions circumscribing “chick lit,” any more than it matters that there conventions circumscribing “westerns.”

What does matter?

- What is the story about?

- When does it happen and what sort of rules govern its characters?

- How well written is it?

And, so YA and children’s writers don’t feel left out: 4. what age group is it geared toward?

Most importantly, all of these considerations are independent of each other, and we should neither assume nor condone the assumption that a story can’t be literary because the main character wears a ten-gallon hat, swings a sword, solves mysteries, flies a space-ship, or has a lot of awesome (or even “terrifying”) sex.

Molly

September 8, 2010 at 9:50 pm

Your graphs reminded me of the “J. Evans Pritchard” scene in “Dead Poets’ Society.” =) I’ve enjoyed reading your post and I think where we make our mistakes as readers (and writers) is in our need to label every work as “this” as “that” or as “the other”. For instance, I’ve been reading a book called Soul Mate by Ronald Lewis Weaver. In short, it’s about a young teacher and her student who share a deep, spiritual connection. As fate intervenes and forces them to collide, it puts them on a path of modern heroism born of their mystical union. Is it romance? Is it fantasy? Is it Esoteric? Well, it’s all of the above, and undefinable at the same time. This, for me anyway, always means a good read.

Christa Polkinhorn

December 9, 2010 at 8:55 am

AMEN. For me the only categories that make sense are “fiction” and “non-fiction.” And then perhaps “crappy books” and “literature,” but even here we get into trouble.

Christa

Fantasy and sci-fi are anthropological – They connect us all together! | J. Nelson Leith

October 14, 2015 at 5:00 pm

[…] may seem obvious that so-called “literary” fiction is anthropological, or perhaps more accurately psychological or sociological, since it so often […]

If Literature Were Furniture | J. Nelson Leith

December 30, 2015 at 1:24 pm

[…] the silly notion that “literary” fiction can’t have sex in it to the facepalm-worthy idea that novels written on cellphones constitute a new genre, we suffer a […]