This is the first installment of my Writing Archetypes series, where I talk about roles, scenes, and plot points that can be found in many stories, synchronizing them with the narrative instincts of the human mind and imbuing them with a distinct psychological presence.

This is the first installment of my Writing Archetypes series, where I talk about roles, scenes, and plot points that can be found in many stories, synchronizing them with the narrative instincts of the human mind and imbuing them with a distinct psychological presence.

You don’t have to be a dyed-in-the-wool Jungian to recognize that archetypes are a core element in storytelling. You don’t even have to like the term “archetype.” Call them what you like: tropes, memes, patterns, threads, modes, models, Platonic forms, şurôt, whatever.

But, no matter what you call them or why they exist, they do exist, and they have undeniable storytelling power.

Let’s start with an easy one. Let’s start with the central one. Let’s start with the Hero.

_

THE HERO

The Hero is not necessarily a brash, warrior type, rushing to battle in defense of the helpless. No cape is required.

The Hero is not necessarily a brash, warrior type, rushing to battle in defense of the helpless. No cape is required.

The Hero, in the storytelling sense, is what you might otherwise call the protagonist, the lead, or the main character, although not necessarily the “viewpoint character” or narrator—if there is one. Sometimes, the Hero’s story is told by or through someone else. The go-to example for this mode of storytelling is Watson and Holmes, but it’s a common style of writing.

The Hero is not always who tells the story, but the Hero is who the story is about.

Focal Character?

Now, you might also have heard of the concept of focal character, which means the role carrying the “excitement” of the story but not necessarily the character with whom the readers/viewers identify. Think Mercutio, or Cosmo Kramer. Although it is undeniable that certain characters can steal the show from the Hero, I consider the focal character idea to be a red herring, as it privileges certain emotional reactions over others and essentially carries no meaning beyond “the writer wrote the hell out of this character!”

That’s not a qualitative character type, it’s a quantitative measure of good writing. Any character could be written so well that he or she grabs our attention, and every character type is the focal point for some sort of emotional response.

The Hero, however, is the focal point for a specific response from the audience that is central to the tone of the story: we identify with her. We put ourselves in her place. Or, we’re meant to.

Protagonist?

Moreover, I know there is a trend to revert to the ancient Greek term protagonist rather than referring to a Hero.

This is ironic, since both “protagonist” and “hero” derive from ancient Greek, and it is the latter that was used in the broadest range of storytelling contexts to mean a main character with relationships to a variety of other characters. “Protagonist” was a technical term for a limited range of storytelling, stage drama, and referred to a single actor alongside one (antagonist) or two (deuteragonist and tritagonist) other actors.

When we talk about the main character today, we clearly mean ἥρως, hero, more than we mean πρωταγωνιστής, protagonist.

The Hero’s Journey is Our Journey

And, although we can try to avoid terms like Hero and Villain as morally biased, we cannot avoid the psychological reality of how the human mind receives those roles in stories. The lead will always be the “stand in” for the listener, by either positive or negative example. We might not always cheer for Heroes, especially the particularly flawed ones, but we do let them zap our mirror neurons with especially powerful zaps.

And why? Because the purpose of any story is to affect the audience in some way, to touch us, and that means to change us. And the best way to change the audience is for the Hero to change while we’re identifying with him or her.

In fact, one good way to identify the Hero in any story is to find the character most altered by what Blake Snyder calls the Transformation Machine. The other characters might change, too, but the Hero’s change is the most drastic, and elicits the greatest identification in those watching or listening to the story.

_

THE HUB AT THE CENTER OF A WHEEL OF CHARACTERS

The most important thing to remember about the Hero, however, is that her role defines other characters’ roles by relation to them. This is why the Hero is a good starting point to introduce other archetypes.

Notice, however, that I did not say the Hero defines all other roles by relation to them. One of the neat quirks about the diversity of genres is that they often conflate, double, or reverse the archetypes on us. The Hero can occasionally steal archetypal energy from (or lose energy to) another role.

For right now, though, let’s just look at the Hero in its basic, unadulterated form so we can see how it is the central archetype of storytelling. We can do this by exploring the contrasts between the Hero and the other archetypes.

Hero ≠ Companion

The Hero is more active (less passive) than the Companion, often called an Ally or Helper. The Companion only takes action to “stick by” the Hero, and to pick him up when his own active energy is waning. This is because, in order for this to be the Hero’s story, the Hero’s action must be what counts.

Even when the Companion takes action, it’s as a surrogate for the Hero when he or she is exhausted or demoralized. Think Samwise Gamgee carrying Frodo on Mount Doom. As Sam himself points out, Frodo is still the Ring-bearer; Sam is merely the Ring-bearer-bearer.

Why did I choose to use the term Companion for this archetype? Etymologically, the word means “one who takes bread with,” a messmate in the military sense. Note how linguistic scholar Tolkien contrasts Frodo’s true Companion Sam from the usurper Companion Sméagol: cursed Gollum is incapable of eating the Elvish bread offered him, and later uses crumbs to make Sam look like a bread thief, and thus a bad Companion.

Hero ≠ Guru

The Hero is more foolish (less wise) than the Guru, often called Mentor. I choose not to use the latter term, as it has been tainted by pop business culture.

The wisdom gap between Hero and Guru derives from the fact that the Hero is the character most changed by the story’s Transformation Machine. For a Hero to grow up, he has to start less grown-up, which means less wise. The presence of the Guru brings this deficiency to the fore and helps the Hero overcome it.

This also explains the typical age gap between the two archetypes, with the Hero being the relative youngster, a factor that is so self-evident it can easily be overlooked. Relative age/maturity becomes quite important, however, when the next archetype is brought into play.

Hero ≠ Rough

The Hero is more naïve (less cynical) than the Rough.

Now, this is a interesting archetypal relationship that’s often missed and rarely discussed. Rough characters are often lumped in with Companions as “Allies” or “Helpers.” But, the role of the Rough is much closer to that of the Guru, because he represents a maturity and understanding of the world that the Hero is grasping for. For the Hero to benefit from a relationship to the Rough, he has to start out less cynical, less streetwise.

And, because of this, the Hero is often a bit younger than the Rough, who is himself a bit younger than the Guru. Think Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, and Ben Kenobi. Noting this three-generation pattern can often help identify an obscure Rough or Guru.

Hero ≠ Comic Couple

The Hero is more serious (less silly) than the Comic Couple, even in a comedy. Not to keep swinging back to Star Wars and Lord of the Rings (I promise to include more realist fiction in later installments) but think R2-D2 and C-3PO, or Merry and Pippin.

There’s a reason why Comic Couple characters are cited as comic “relief.” They provide a laugh after all the serious stuff the Hero is up to.

Hero ≠ Villain

Finally, the Hero is more sympathetic (less hostile) than the Villains, even when the Hero is a so-called anti-hero.

To put it simply, all of the other archetypal roles are defined in relation to the Hero. They might be secondarily comparable to each other, but it is the Hero who is the hub at the center of the story’s wheel of characters.

_

WHERE’S HERO?

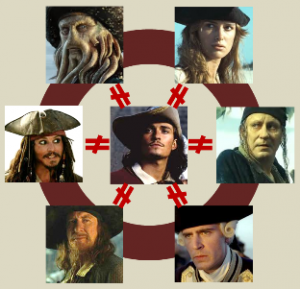

But, to make sure we know how to peg the right character as the Hero, it’s important to find an example where we might get confused. So let’s take a look at a deceptively simple story, the original Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy.

I bet you think Jack Sparrow was the Hero of those movies, don’t you? Not a chance. He’s the Rough, and one of those scene-stealing “focal characters,” but he’s not the Hero of the story because he changes very little.

I’ve also read that Pirates screenwriter Terry Rossio thinks that the longer story arc in the trilogy was about Elizabeth Swann. If he thinks that, it’s good example of how stories are often deeper than the conscious intention of their creators. I understand the drive to have a female Hero, but that’s not what’s really going on in the Pirates trilogy, even if that’s what Rossio and company were attempting to do.

Elizabeth is a very close Companion, sharing a lot of the Hero energy, but it is Will Turner who goes through the greatest transformation in the core three films, not Elizabeth. She might become the “Pirate King” at the end, but she was already dreaming of that lifestyle as a little girl in the opening scene of the trilogy. Will has to struggle with his identity and outgrow his naïve antipathy toward pirates. Will is the one with a “touch of destiny,” and Elizabeth’s stint as the leader of the pirates simply carries him to that destiny.

Will has to explore his mysterious parentage (calling Joseph Campbell!), question his allegiances, over-promise himself into quests larger than he can handle, and struggle to differentiate himself from the other characters. That is, in relation to the other characters.

H e is “not like” Jack, as he insists: not as cynical as the Rough. He won’t stay idle while Elizabeth is in danger, as he believes Norrington will. He won’t abandon Bootstrap the way Bootstrap left him behind. He won’t corrupt his duty the way Davy Jones did. He won’t be tempted by treasure as Barbossa was, at least not the golden kind.

e is “not like” Jack, as he insists: not as cynical as the Rough. He won’t stay idle while Elizabeth is in danger, as he believes Norrington will. He won’t abandon Bootstrap the way Bootstrap left him behind. He won’t corrupt his duty the way Davy Jones did. He won’t be tempted by treasure as Barbossa was, at least not the golden kind.

Will is defined by relation to all of the other characters, and therefore they by him. He is the true hub at the center of the Pirates trilogy.

Elizabeth’s relationships, on the other hand, only matter by reference to her relationship with Will. This is perhaps (politically) unfortunate, but true. When she flirts with the idea of being with Jack, it is only to reaffirm her ultimately sticking by Will as his Companion. When she is captured by Barbossa, it is because the pirates have mistaken her for Bootstrap’s real heir, Will. And note, when Barbossa offers her food (including bread!) she suspects that it’s been poisoned.

In every case, right up to the end of the trilogy, Elizabeth’s energy sticks to and supports Will’s. If Rossio really believed he was writing the Epic of Elizabeth Swann, well … God bless ‘im, but she falls quite short of being a genuine female Hero.

Will Turner, for better or worse, is the Hero of Pirates 1 through 3.

_

Top Picks Thursday 11-21-2013 | The Author Chronicles

November 21, 2013 at 1:05 pm

[…] Renner reminds us not to stop the action to introduce each character; J. Nelson Leith discusses the Hero archetype; Amanda Bumgarner lists 3 pitfalls of foreshadowing; and Victoria Gefer examines how much […]

How the damsel stereotype tricks us into rescuing it from our own attempts to destroy it | J. Nelson Leith

December 5, 2014 at 12:27 pm

[…] I’ve discussed before, archetypes exist in relation to one another. This is especially and necessarily true for those […]

Tim Hunt and the danger of the Damsel Bias | J. Nelson Leith

July 2, 2015 at 5:29 pm

[…] we discussed the Hero archetype, I emphasized that the defining characteristic of the Hero is that he or she is the hub at the […]

Writing Archetypes – The Proximate and Ultimate Villains | J. Nelson Leith

July 22, 2015 at 7:25 pm

[…] Heroes often start their stories in a state of innocence and ignorance. As we’ve seen before, the Guru often has to bring the adventure to her. Something is wrong in the world, the Guru knows, and the Hero is the key to fixing it. […]